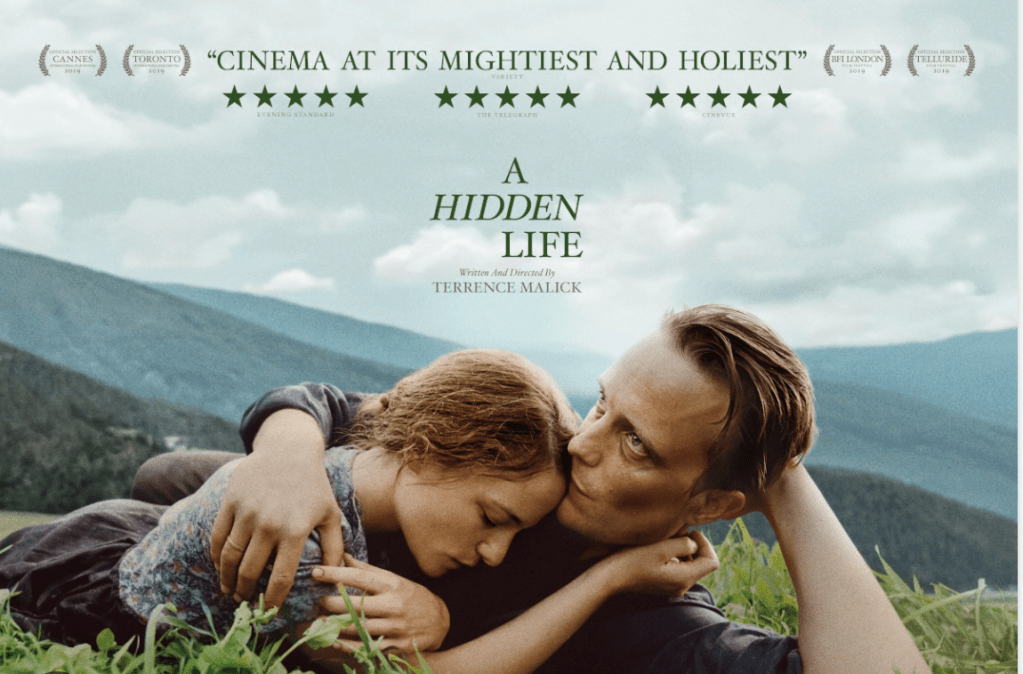

“For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God”, says the Apostle (Colossians 3:3), a truth proclaimed in the 2019 motion picture, “A Hidden Life”. Within this masterpiece, beauty manifests itself in various forms; nature, family, virtue, faith, and art being a few. Above all, the film portrays the beauty of death as the highest achievable transcendent good—and not mere bodily death, but death to the self.

The opening scenes featuring the beauty of the earth, and the pure, intimate, contemplative shots of the village life combine to give the viewer impressions of bliss amidst hints of future calamity. As the film progresses, however, confidence in the power of “good” falters and wanes. The main couple, Franz and Fani, do not simply battle the pressures of the Nazi government, but begin to face ostracism within their own community. Scenes of glorious natural landscapes contrast with the ugliness of human failures. The only continuous stream of beauty that persists is the life of Franz, as well as Fani’s willingness and courage to join him in his sufferings.

Within the Christian philosophical and theological tradition, the idea of seeking out the form of the “Good” itself— pursuing ultimate “being” of Good for the sake of this selfsame and complete Good—is consistently reoccuring from a historical perspective. Franz’s life reflects the trajectory of the ‘examined life’: “What good will your sacrifice be to anyone?”, he is asked countless times. What these inquisitors fail to realize is that Franz’s concern lies with the beauty of pure Justice itself. According to him, all goodness ultimately finds its origin and destination in God. Refusing to conform one’s identity and the root of all one’s actions to the character of God eliminates all sincere goodness. That is the beauty of Franz’s heart—the desire to uphold goodness despite opposition and persecution. “There is a difference between the suffering we cannot avoid and that which we choose”, an interrogator sneers at Franz derrogatively. Despite malicious intent, his statement is perhaps the highest praise Franz could receive. He imitates Christ’s life so fully that he opts to bear his own cross. Just as the crucifixion itself is beautiful because of the meaning of Christ’s sacrifice, scenes displaying Franz’ horrible detainment become wondrous due to the Scriptural passages Franz quotes, illuminating his perspective of the Passion and boldly giving himself up to death like His Savior.

On a slightly unrelated note, the scene with the cathedral painter (early in the film) might be one of my favorites. Painting a “comfortable Christ” may be the burden we unwillingly carry our entire lives. Undoubtedly, Franz paints the very life of Christ with the beauty of his devoted heart. Yet the unnamed artist invites us to question the purpose of religious art itself. Can we truly identify with the suffering of those figures we claim to hold in such admiration, or do we pride ourselves in shallow sympathy? Can art itself serve to instigate change during oppressive circumstances?

In sum, the substance of Franz and Fani’s integrity sparks an understanding of what it truly means to live a good and blessed life. Franz’s courage to embrace physical death, as well as his daily offering of himself in love, reflects the grandeur of divine beauty, and Fani’s sacrifices as a wife and mother are essential to this ultimate picture as well.