Keats listening to a Nightingale on Hampstead Heath

Sunday Morning, by Wallace Stevens

To Autumn, by John Keats

“Death is the mother of beauty”, says Wallace Stevens, completing the thought initiated by his precursor, John Keats, when he stated, “‘Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty.’ – that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” at the conclusion of his poem ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’. Despite being a Modernist, Wallace Stevens was greatly inspired by the Romantics, a fact made evident by merely analyzing his poetry. Although one might easily identify the Keatsian parallels in Stevens’ poetry, I will argue a more profound assessment reveals that Stevens in fact amplifies, redefines, and transcends Keats’ original import. Investigating both the similarities, and especially, the contrast between the poems ‘Sunday Morning’ and ‘To Autumn’ demonstrates this point precisely.

“To Autumn” is one of the most perfect descriptions in the English language not only of the abundance of the season but also of the melancholy atmosphere of nostalgia. Within the very first verses, Autumn appears personified as a beautiful woman, an intimate companion of Summer, who sometimes works with him so that the vines fill with bunches and the apples ripen, sometimes falls asleep in the field, numb by the aroma of poppies. This celebration of Autumn, personified and carrying pantheistic overtones, is naturally not exclusive to Keats, as both William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge also wrote variations on this subject. However, two elements make the selected ode superior: the harmonious connection between nature and the “mental landscape” it evokes; and the vivid detail and sensuality present within its bucolic images. Autumn appears essentially linked to melancholy, evoking memories and meditations about existence. Such melancholy is intimately connected to human ephemerality. The awareness that everything is perishable generates sadness, but also a desire to “seize the day”. The poet exhorts the reader to seize the moment, triumphing over melancholy. It makes one more sensitive and therefore able to better appreciate the bitterness and the sweetness of existence.

The lament for death that autumn announces invites one to celebrate life even as it melts and, heroically, persists shedding its dying colors. The green turns to yellow, red, and orange that cultivate the beauty of vibrancy, proclaiming its last breaths to the sun. It approaches divinity and touches the crevice from which the secrets of death are released, just as closing one’s eyes in front of the sun reproduces the mixture of colors that appear when opening the same. Nevertheless, the death of the leaves remains nature’s final sigh. Indeed, nothing is needed to complement Keats’ ethereal image. However, Wallace Stevens succeeds in amalgamating this revelation together with his own philosophy; yes, Stevens remarks on the short-lived nature of life, but he also adds his reflections on the inseparable unity of artifice and medium, much like their unity in the art of painting.

In a speech given at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1951, entitled “Relations between Poetry and Painting”, Wallace Stevens argued that, in an age of disbelief such as ours, art would work as compensation for what humanity had lost and imagination would now reign supreme, whereas before, faith had occupied such a space: it would, therefore, be up to poetry and painting, artistic forms that operate between imagination and reality, to assume their “prophetic role” and become a “Vital assertion of self in a world where nothing but the self remains, if that remains.” (Stevens 171).

Avoiding further explorations and explanations about the poem (“once a poem is explained, it is destroyed” Stevens stated in a letter), I would like to approach it from an analysis that approximates it to painting. Stevens’ poetry simultaneously incorporates conflicting elements of impressionism–colors, light, air, impressions, the passage of time (both chronological and climatological)–and cubism–the implosion of the object, mutation, explosion of points of view, simultaneity–in his poetic work. Therefore, he works between nature and artifice, between charm with appearance and the metamorphosis of appearances. Stevens’ sensitivity would therefore be linked to the idea of change. On the one hand, impressionism, with its passive principle of change; on the other, Cubism with the active principle of imagination. Thus, the metaphors of poetry and the metamorphoses of painting draw on the same reservoir of analogies.

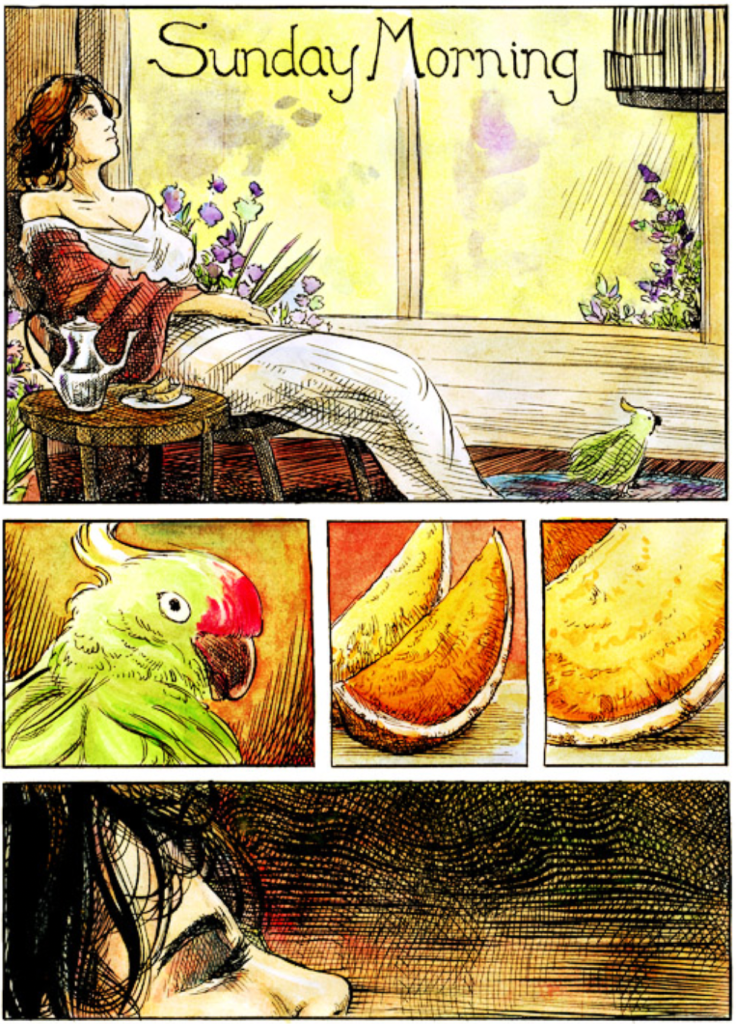

The poem is a meditative monologue, sometimes in the first, sometimes in the third person. Superficially, it is tied together by references to the central female character: she dreams, she thinks, and she inquires. The character is even emptied of her humanity, without physical characteristics that distinguish her; as in a work by Matisse, she was sacrificed in order to become a decorative pattern. Nevertheless, the author indicates that the poem is not a discursive presentation of arguments with a dialogic evolution–it is in the realm of rhetoric, and not dialectic, that Stevens stages his battle. The central character loses her prominent role, and the narrative fabric is torn. With that, the idea of unity that the poem presents would not be in the female figure, but in its pictorial composition; “Sunday Morning” is not a succession of ideas, but of frames. The first stanza is organized as a diptych: on one panel, the woman sitting on the chair, oranges, the cockatoo, arranged à la Matisse on an oriental rug; in the other, a gloomy lake. Silence accentuates the pictorial characteristic, as well as the spatial notion provided by “As a calm darkens”, and prolonged by, “the day is like wide water”. Such an antithetical pattern, an image of earthly life and a supernatural scene, continues in the following six stanzas and resolution occurs in the last stanza, corresponding directly to the initial diptych, but in reverse order: a formal ordering in the chiasm, raising our aesthetic appreciation for the poem and the balance of the composition.

The effect of this pictorial method would seem to introduce tension to such a balance. However, the atmosphere of “Sunday Morning” is not tense, and Stevens is not a dramatic poet. Tension, then, is spatial, arising from the juxtaposition of antithetical blocks. The sequential pattern of the poem, therefore, proceeds in a perfect circle. The strength of the poem indicates that it achieves an emotional impact coming from within the daydreams of a meditation that is inconclusive and circular. It represents the triumph of an undramatic poet over his own limitations. Stevens, gifted with a powerful visual imagination, presents the conflict of ideas as the conflict of forms.

In Stevens’ case, we are not confronted by the pictorial environment that the poem sets in motion, but it is the sound surface of the language that dominates our attention. Sound is the medium, as paint is for, say, Picasso (or Matisse or Manet); we are absorbed more by lexical texture and the most variegated syllables than by statements, placements, or semantics. Words build a double relationship in which language is both referential and self-referential, reiterative and mutative in terms of sound and meaning.

Thus, I would like to propose a relationship between this poem and the genre of still-lifes. Quite focused on interior spaces and, for the most part, domestic spaces, the still-life painting can present the placid and cozy life of the home through the mediation of objects. It is the artist’s retreat, not as escapism, but as a way of strengthening his spirit for the daily battles against the “pressures of reality” (Stevens 1951: 13). It is in such an environment that profound meditations take place, in such as those proposed in the first stanza of “Sunday Morning”. More than just a composition by Matisse, it is likely the lines that open the poem construct the exact image of a still-life: fruits, vases or mugs, the tapestry; even the exotic bird would not be an unusual item in this genre of pictorial art. If, on the one hand, historical painting is built around a narrative, “still-life”s are the world subtracted from its ability to create narrative interest. Furthermore, Stevens is not working within the (temporal) relation of the dialectic, but rather with the almost immediate presentation of self-centered rhetorical frames; and, if the principal female character is emptied of her predominant role, and the removal of the human figure is the founding principle of the still-life genre, we may then conclude the poem then appears to be constructing a still-life. It is a representation of those things that lack importance, the unassuming material basis of life, (i.e., the orange, the coffee, the cockatoo)–and the representation of things in the world that demonstrate grandeur (the ‘ancient sacrifice’, the ‘dominion of blood and sepulchre’). The equality of importance between these two modes, achieved by being joined together, causes the narrative scale of human importance to be broken. If in the narrative what matters is the conflict and change, in the rhetorical presentation of the poem, narrative is useless. In the still-life, there is no spiritual “Event” and, likewise, the woman chooses not to participate in the grandiose and megalographic narratives of the Church, deciding, on the contrary, to stick with the trivial, with things, with the topographic.

This abolition of the distinction brought about by the representation of mundane and base things in still lifes poses a threat to representations that consider themselves superior to others, that believe to have absolute access to exalted and elevated modes of existence and experience. There is in commonplace objects a level of simplicity, in the representation of shapes that is “virtually indestructible” (shapes that resist the passage of time practically unscathed: fruits, flowers, cups, plates, pitchers); there is in them a level of familiarity of forms that are legacies; these objects are tied to actions repeated by all their users in the same way, across generations, presenting the lives of ordinary people more as a matter of maintenance and repetition than of originality, individuality, or invention. And it is precisely this threat to grandeur in the face of everyday objects that Stevens is carrying out in the eighth stanza.

It seems that Stevens loosens the diptych separation present in the poem and instead paints a single picture that presents the simultaneously supernatural and natural, the base and sublime. This approximation can be observed in the relationships between words used in the first half of the stanza that echoes words from the second half, namely, “unsponsored” echoes in “spontaneous”; “island solitude” in “isolation of the sky”; “chaos” into “casual”. These relationships tie together the stanza–even though it is organized as a chiasm of the initial stanza–and unite elements that were previously disparate and disconnected enough to characterize a couplet. Furthermore, Stevens culminates the stanza and the poem with a chain of trivial and natural things–the roe deer, quails, mountains, wild fruits, and pigeons–thus granting greater weight to the common and low elements than to the extraordinary and elevated ones, inverting the value usually given to each of these sides (normally, narrative paintings have more prestige while still-lifes are relegated to a lower position within the world of art). This approximation of the elements on both sides of the stanza, together with the topographic climax–the focus on the trivial–, pose a threat to the elevated, to narrative, and are therefore structurally connected to a variety of still-lifes.